For a Human-Centered Design

“We design our environments and thereby design ourselves.”

Why does design matter? Why do we as designers spend so many hours upon hours in these processes—interviewing users, analyzing their responses, iterating, iterating, iterating, and pushing some more finalized prototype through to further perfection and implementation? Designers seem to know that we are not merely creating shrines to the sticky-note gods deep into the night in fervent plea for some revelatory insight to reframe the entire problem just for its own sake. We seem to know that worrying over the perfection of pushed pixels is not entirely, completely analogous to Sisyphus’s plight—that we are working toward something bigger, that there actually is a future for us over the hill. Possible immediate responses are to solve problems or to make things work better. Why? we might still ask. To what end? Someone has the more specific response, to make our users’ lives work better or to respond to our users’ problems or to delight our users. And there it is—the purpose and the consequence of what designers do, the reason for it all. The users.

And the truth, I think, is that the work of designers is even more far-reaching than we might suppose, and that this consequence of design conveys even more gravity to consideration of its purpose.

We design our environments and thereby design ourselves.

Humans act based on how they perceive the present in light of their previous experiences. Every experience has the potential to change a person’s perspective on the world in the present moment and every point in the future—and how they act in every subsequent moment. These present experiences are sometimes dictated, but at minimum influenced, by the features of the environment in which they occur, including human-designed features—a building, a sidewalk, a piece of art, a billboard advertisement, a mobile smartphone app.

On the other side, the features that someone adds to the environment are informed by the way in which that individual perceives the world—an outlook that is, again, influenced by their previous experiences. As we add features to our environments, we add features that have the power to impact others’ perspectives on the world; to change the ways in which they both subsequently interact with the existing features of the environment and the features that they add to it.

The history, present, and future of society is in this way a self-perpetuating succession of perspectives influencing designs influencing others’ perspectives. Designs are thus powerful: they influence the outlooks of the members of society, which is both important both intrinsically—we care how our perspectives are shaped for their own sakes—and instrumentally, as each member’s outlook will partially determine the further design of that society. Design choices matter for how we understand the environment around us, ourselves, and others, which determines in large part how we engage with and relate to the same.

These are heavy consequences: no less than the progression of human history itself. Because design has this transformative potential, I argue that designers should consider the users—that is, those who will use, view, or otherwise interact with their designs, which will in all likelihood occur via the implementations of the design out in the world—first and foremost at every point in the design process. A user-centered purpose to design should be considered first of all. I argue that it is the role and responsibility of the designer—architect, artist, anyone who changes the environmental features of society—to design with those who will interact with their designs first in mind.

THE ETHOS OF TRANSFORMATIVE DESIGN

This understanding of design as capable of defining great personal and (thus) societal change was characteristic of the Modernist ethos, culminating in the Bauhaus school of the early twentieth century. Modernists viewed designed environments to be expressive of the ways in which we would like to see society transform—and, even more importantly, as transformative themselves.

Senior Lecturer of Art History at Dartmouth College Marlene Heck proposed that we consider Modernism an attitude, a way of thinking and being, that typifies this mindset. [i] Heck argued that Modernism in this sense arose from the Enlightenment idea that we can rely on our reason to understand the world in all its complexity. More fully, this idea maintains that we both understand through reason and, further, act according to this reason to change the environment in such a way that other members of society can (1) interact with that change and (2) be changed by reflection on it through their own faculties of reason. These first Modernist architects and designers were arrested by the belief that the right architectural environment has a beneficial effect on those reasoning beings who view or use it—and that the converse is true with poor design.

It certainly seems true that this principle of the transformative power of design extends farther back in history than the Bauhaus. The idea appears even in Plato’s writing: in The Republic, Socrates and Glaucon discuss the ideal city, and how its precise composition—including the types of art and other human-created artifacts it may contain—will or will not be conducive toward human living and flourishing. [ii]

“Designing for humans requires conviction of the way humans are.”

Importantly, it is especially clear in Plato’s writing that designing for humans requires conviction of the way humans are and the ways in which certain traits and perspectives can be cultivated in them. [iii] Plato, for example, argued that humans have tripartite souls (rational, spirited, appetitive) and are teleologically oriented toward flourishing. [iv] On this ground, Plato maintained that the design environment should cater to each of these three parts of the soul and create the conditions for flourishing for each human individual: in this way, his understanding of human nature grounded his understanding of what good design is, and what a well-designed society looks like.

Of course, the approach to design as transformative was especially explicit in the Modernist period. Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus school of design, wrote of an aesthetic that meets “material and psychological requirements alike”—good for human functioning as well as “the human soul.” [vi] The principles expressed in the work of the Bauhaus maintain that functional simplicity, flexible open spaces, and natural light, for example, are good for humans [vii]—once again, we find that the designers’ conception of human nature define their design principles.

It was part of the Modernist architectural ethos to design everything about a building—down to the screws—to be maximally conducive to human living; in a severe break from this total design principle, and moreover from the idea that design should be user-centered at all, Postmodernist architect Peter Eisenman maintained that architectural design occurs in the mind of the architect, and implementation of those designs into actual buildings is beyond the purview of the architect. [viii] Accordingly, Eisenman was completely disinterested in the humans who might one day interact with an instantiation of his designs. House III, for example, with its rotated grid within a grid and consequentially small triangular and sharply angled trapezoidal spaces, is clearly not intended to be optimized or even conducive to human use.

That said, Eisenman seems to be in the minority of architects who feel it is not part of the business of the architect to consider how his ideas might be implemented in the real world; most seem to view human user as fully embedded in the entire process of architecture, from initial conception through use of the implementation. Robert Venturi, for example, explicitly calls for architecture that creates “meaningful contexts” through the organization of parts within wholes to bring “satisfaction” to those who interact with it. [xi] Frank Gehry also clearly includes consideration of human scale, form, and eventual use in his architectural design. The tiny figurines in the early versions of his models stand as sure evidence of this consideration of human scale and form [xii]—and he uses that understanding create unexpected, vast forms to instill that eventual human user with the sense that this building is, in the words of one of those users, “‘an arena where something incredible could occur.’”[xiii]

Architect Frank Gehry used his understanding of human scale to create unexpected, vast spaces to inspire awe in users, such as the above pictured Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain.

Gehry was able to create the healing spaces of the above pictured Maggie’s Centre in Dundee, Scotland only by his conception of the its eventual users: cancer patients such as his dear friend Maggie.

Only with his understanding of his eventual users is Gehry is able to design spaces that relate to healing—the prime example being Maggie’s Place in Dundee, Scotland, a restorative center for cancer patients. Patients and their families describe the building as being conducive to reflection, humor, and informality in a way that allows them to “see their illness in a context which is bigger than themselves.” [xiv] The design of this building clearly has transformational effects on those who interact with it—because the designer kept his friend Maggie Keswick Jencks and all patients like her first in mind when designing it, fulfilling his role and responsibility as a designer, the building’s effect is a positive one.

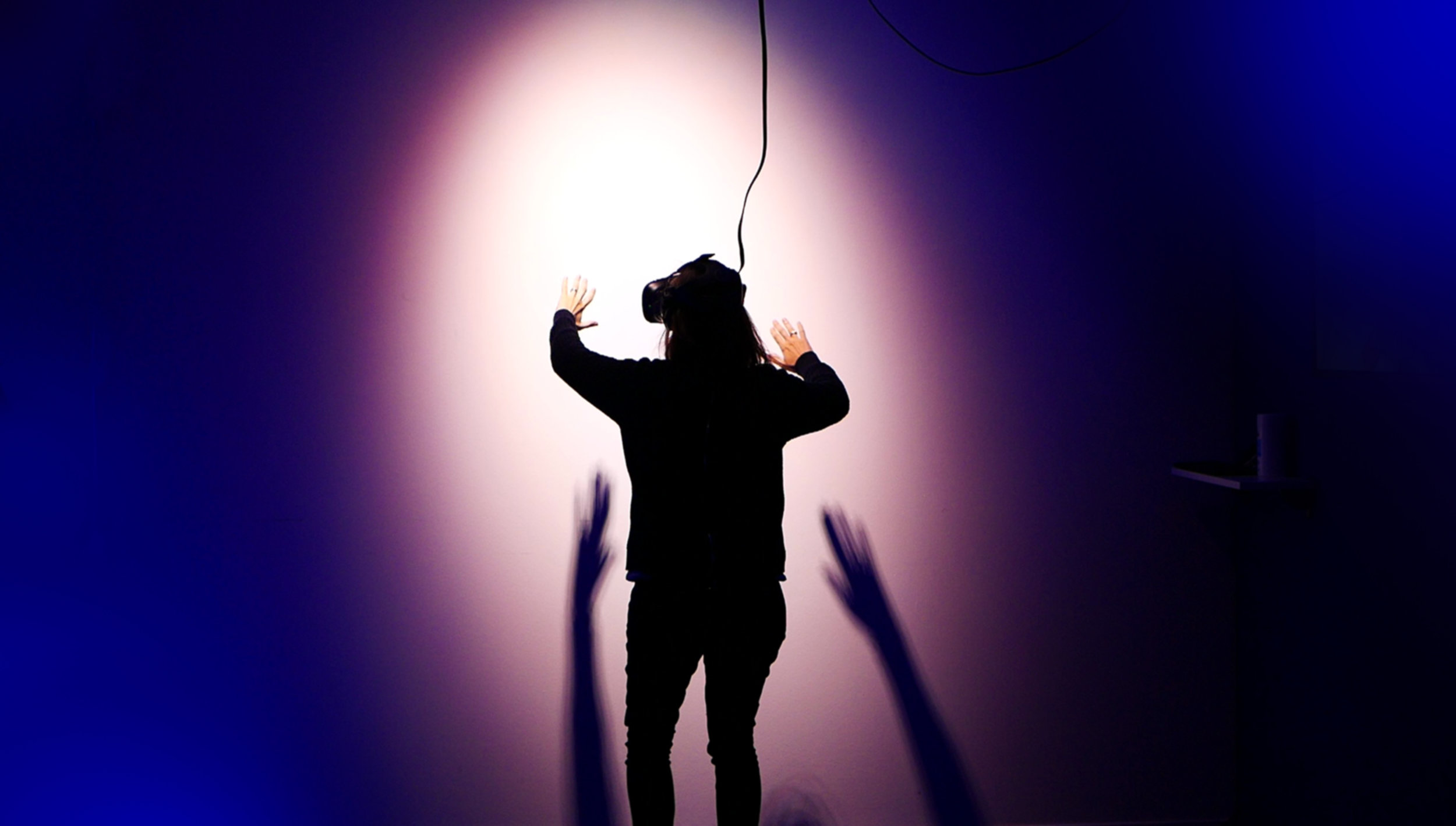

Innovations in film likewise illustrate the idea of user-centered design. Media theorist Kath Dooley posits that user-centered considerations are of particular import in 360-degree cinematic virtual reality (VR). [xv] For example, the filmmaker must adopt tactics to direct the viewer’s attention when the filmmaker has inherently much less control over it, given the freedom that the 360-degree environment allows the user.

In the case of VR, the user is literally in the center of the experience—they are surrounded by the narrative on all sides—so the designer must adopt tactics to direct the viewer’s attention in a very specific way. This process is a good illustration of the approach that should define all design.

In the case of VR, the user is in some sense literally in the center of the experience: they are surrounded by the narrative on all sides. That said, it seems that all filmmakers must similarly consider the viewer to be at the center or at least end of their craft: they must consider the viewer’s experience and reactions to the story as it unfolds, to properly complete their task as filmmakers. It would be strange, on the other hand, to say filmmaking occurs in the mind of the filmmaker, or even on reels of raw footage—rather, film seems to occur in the way footage is cut, edited, to best represent its content to viewers.

For instance, in the most basic sense, filmmakers’ consideration of anticipated viewers is demonstrated in methods to increase film legibility. In the 1908 Pathé Frères film The Physician of the Castle, for example, use of technology with which the filmmakers knew the audience was familiar, the telephone, made possible the legibility of the melodramatic cross-cut climactic montage, at a point in film history where audiences were used to long continuous shots of footage and would have otherwise had trouble deriving any understanding of the film at all. [xvi]

Not to say that all films should be perfectly understandable to the anticipated audience—but such a design choice is also made with that audience in mind. For example, in his 2018 film The Image Book, Jean-Luc Godard provides the English-speaking audience with inconsistently present subtitles over French dialogue, not providing translations for every piece of narration, leaving the viewer to wonder whether she has the entire story. This technique serves to underscore one of the major themes of the film, that humans should not trust an easily manipulated reality as much as they usually do.

Again, crucially, both filmmakers draw from some of their own ideas of what humans are like: in the Pathé Frères case, that humans are accustomed to a perception of the environment that is continuous across space and time, and familiar with the telephone (at least in the case of the intended audience), and thus unprepared for the cross-cut across space, but able to use the telephone as a cue to make sense of it. In the Godard case, gullible, and in need of disruption from complacency.

VR film may have a special status due to the explicitly interactive nature of the medium, but its user-focusedness does not seem particularly unique within the greater context of film—nor within the greater context of design.

HUMAN-CENTERED IMPACT DESIGN

Design changes, disrupts: whether intended or not, each design choice has a pervasive effect. On this basis, I propose that it is the role and responsibility of the designer to consider the potential effects of their designs on those who will interact with them.

Critically, as we have seen, the form of our designs for users hinge on what beliefs we have about the users. These beliefs range from more deep-seated convictions of human nature to ideas about human psychology and behavior to our understanding of a specific user’s perspective and processes in the world. Designing for the users necessary begins with and is determined by this understanding, which should consequently be responsibly established and likely routinely examined in the first place—through casual and/or formal examination of human nature, through user research, and user testing throughout the design process.

It seems that in most cases designers are aware on some level that they have this role, and that the idea of making design choices with intentional consideration of how they might affect the intended audience is not novel. The recognition of the importance of user research and testing seems present in most spaces today, for example. My discussion aims to make this understanding explicit and to prod the far-reaching more abstract consequences of the idea, and to oppose conceptions of design that are more purely theoretical, like Eisenman’s, as well as even the notion of design as problem-solving that is prevalent in some industry spaces today. Responding directly to the latter, Andrew Salituri recommends that design outcomes are better framed as responses to the problem rather than solutions, and that design is likewise better framed as change rather than problem-solving, keeping in mind the intricacies of the changes instigated by every design. This idea is very much in line with my discussion here; I would only emphasize what I see as the greater point: the changes designs instigate have effects on the users, and it is these people designers should strive to have first in mind when bringing about change in the world.

Design is change to the environment, which affects the way users interact with that environment, their experience with it, and thus their worldview as influenced by that experience. It is the role and responsibility of the designer to consider those who will be changed by their designs, first and foremost, from conception through implementation: for by designing anything, we design ourselves.

[i] Marlene Heck, “Modernism” (lecture, “Humanity By Design,” Hanover, NH, April 15, 2019).

[ii] See e.g. Plato, The Republic, Bk II 368a-381e; Bk III 368b, 400e-402c, 403c-410b; Book IV 420b-425e, 427e.

[iii] Sam Levey, “Plato” (lecture, “Humanity By Design,” Hanover, NH, April 8, 2019).

[iv] Plato Bk IV 436b-441c; Sam Levey, “Plato” (lecture, “Humanity By Design,” Hanover, NH, April 8, 2019).

[vi] Walter Gropius, “On the Bauhaus,” 1-2.

[vii] E.g. pilotis to make walls “mere screens” (Gropius, 1) and more flexible in their construction; ribbon windows allowing rooms to be “much better lit” (Gropius, 1); flat roofs to avoid wasting space in “unutilizable corners” (2) and for “the elimination of unnecessary surfaces” (Gropius, 2); and emphasis of “spatial harmony, repose, proportion” (Gropius, 3) throughout.

[viii] Samuel Levey, “Eisenman” (lecture, Humanity By Design, Hanover, NH, May 6, 2019).

[xi] Venturi, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (1966).

[xii] Sketches of Frank Gehry. Directed by Sydney Pollack, produced by Ultan Guilfoyle,

2006. Vimeo, uploaded by Ultan Guilfoyle, January 23, 2018, https://vimeo.com/252370825, 1:01:59-1:02:19.

[xiii] Sketches 41:12-41:20.

[xiv] Maggie’s Place (2002); Sketches 1:08:30-1:09:48.

[xv] Dooley, “Storytelling with virtual reality in 360-degrees: a new screen grammar.” Studies

in Australialasian Cinema 11 no. 3 (2017): 161-171.

[xvi] Mark Williams, “Modernity and Modernism” (lecture, Humanity By Design, Hanover, NH, April 1, 2019).